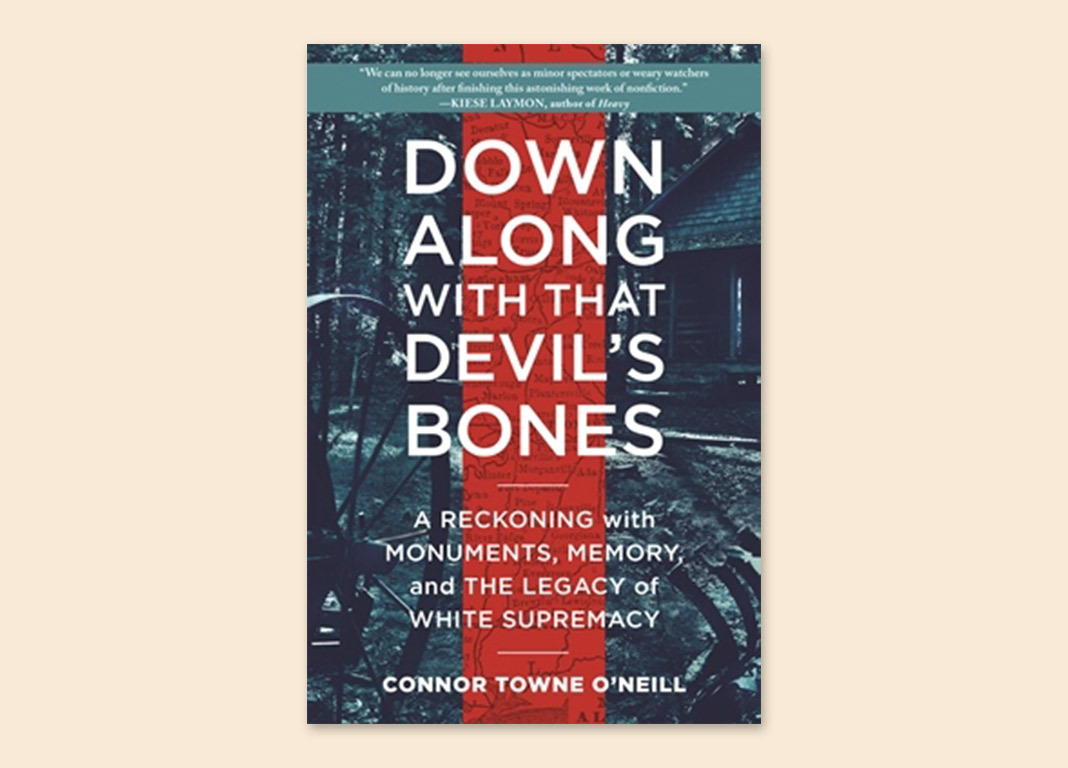

Every Thursday at 4pm, as part of its series Literary Thursdays, the library hosts an author to discuss their book. On Thursday, October 8, Connor Town O’Neill spoke about the process of writing Down Along with That Devil’s Bones: A Reckoning with Monuments, Memory, and the Legacy of White Supremacy. The book, which traces the struggle in four cities with four monuments to notorious but revered Civil War general and Ku Klux Klan leader Nathan Bedford Forrest, began in a cemetery in Selma in 2015, where the Friends of Forrest were preparing to install a statue to the war criminal and slave trader. It was the 50th anniversary of Bloody Sunday in Selma and, among the magnolias and Spanish moss, O’Neill wondered what this juxtaposition said about the country.

O’Neill began following campaigns to take down statues to Nathan Bedford Forrest, believing such statues are “double-jointed,” reflecting the times they go up in as much as the history they represent. The activists lobbying for the statues’ removal were taking on systems of power and people that turned on questions of whiteness and for O’Neill this began a process of personal reckoning as he scrutinized the role of race in the United States.

The statue in Selma first went up in 2000, when Selma’s first black mayor, Reverend James Perkins, Jr., was in office. Perkins told O’Neill it was a “pronouncement of war.” The 400-pound bust was stolen in 2012. O’Neill believes that what happens in Selma is a harbinger of what is to come in the rest of the nation – it is “revealing and prophetic,” he says. For example, in the 1990s Selma went through an intense battle over school desegregation that later played out around the country.

Another campaign O’Neill followed addressed the Forrest building on Middle Tennessee State University’s campus, which housed its ROTC program. Students staged a burial of an effigy of Nathan Bedford Forrest in 2015, later leaving his body on the stoop of his hall. One-third of MTSU’s student body is black. Student activists alleged that the Forrest name represents white supremacy, given Forrest’s history as a slave trader and his prominent role in the KKK, while others asserted that Forrest was the savior of the town by driving out the Union in 1862. “His spirit has always been close at hand,” was said when the building was dedicated mid-twentieth century. Memories, says O’Neill, are polarized.

We remember, he says, by forgetting, which allows white southerners to rally behind the phrase “heritage not hate.” White Americans, O’Neill believes, have a selective history about a war that was waged based on the notion of blacks’ inferiority.

O’Neill also related the story of Memphis, where the city government came up with a clever plan to remove the Nathan Bedford Forrest monument – by selling the statue to a non-profit, which wasn’t prohibited from taking it down. One of the longtime protesters remembered crossing the street to the park the night the statue was taken down and how the street seemed wider than an ocean.

O’Neill shared that victors in wars often have an interest in removing symbols of the losing side. The fact that so many monuments to Confederate leaders from the Civil War exist suggests to O’Neill that “they didn’t lose as much as we thought,” as their ideology is still alive. The author asked if it is possible to create an equal society if we haven’t reckoned with the consequences of the Civil War. He explained the role that race has played in his own life, from housing laws that favored his white family to his family’s ability to use that collateral to take loans for his education. “The main driver of American wealth is driven by race,” he says, referring to home ownership.

We need, says O’Neill, to get over the notion that the past matters to remind us how great we are. And, he spoke against the notion that racism is somehow a problem only for black people, indicating that it impacts us all.

Confederate statues, he says, gesture to the present in an electric way. If you think such a statue is repugnant, ask yourself why and what implications that might have for your life and society at large. While O’Neill believes that campaigns against symbols of white supremacy will continue, he hopes such efforts will draw us into changing policies and into deeper conversations that are waiting for us.

Check out the eBook here.