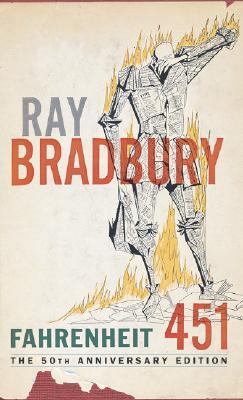

As a part of The Big Read--a national movement aimed at creating a country of readers--in libraries across Queens, we are reading and delving into the themes of the classic Fahrenheit 451. We will explore Ray Bradbury's novel--a character-driven, thought-provoking read set in a dystopian future world that is still recognizable--through free book discussions, film screenings and more community activities open to any and all in the community.

Read the book and want to sink your teeth into another novel that makes you think and assess your own values? Try these:

1984 by George Orwell

"'Big Brother' is watching" has become a catch phrase in our society. 1984 and communism may be in the past, but the ideas in this book remain relevant.

Atlas Shrugged by Ayn Rand

John Galt said he would stop the motor of the world that penalizes human intelligence and creativity.

Brave New World by Aldous Huxley

What kind of individuals arise from cloning, feel-good drugs, anti-aging programs, and total social control?

Lovestar by Andri Snaer Magnason

Technology, advertising, and mass media are ever present in this world where even love is regulated by science.

Oryx and Crake by Margaret Atwood

Explore how runaway social inequality, genetic technology, catastrophic climate change, and an effort to improve mankind culminate in an apocalyptic event.

Shades of Grey by Jasper Fforde

Not to be confused with the erotic novel 50 Shades of Grey, Fforde explores a world where social castes and protocols are rigidly defined by acuteness of personal color perception.

When She Woke by Hillary Jordan

A young woman awakens to a nightmarish new life; her skin has been genetically altered, turned bright red as punishment for the crime of having an abortion.

Can you think of any others? Add your suggestions in the comments below.

To celebrate Cinco de Mayo, on May 5, children at Queens Libraries at Steinway and Sunnyside made a unique craft project: "ojos de Dios" (translated: God’s eyes) ornaments. Cinco de Mayo--a chance for us all to celebrate Mexican culture, freedom and democracy--originated in the Mexican state of Puebla and is a holiday that symbolizes pride in Mexico and its people. Keeping with our theme of creating environmentally-friendly crafts, we used old popsicle sticks and leftover yarn to create these beautiful ornaments (pictured here).

For those of you who don’t read their almanacs every day, May is National Hamburger Month. Why should you celebrate a food item that saturates our culture? At the very least, you can learn how to make a better burger yourself. But thinking about the humble hamburger can also inspire thought and discussion about American identity.

The hamburger, despite a name that seems to derive from a German city, is a particularly American food. It requires minimal cooking and the assembly of many simple, raw ingredients. Convenience and affordability are pretty American.

In the enlightening Hamburgers & Fries, John T. Edge explores the origins and varieties of hamburger with wit and an eye for a good recipe. As Edge observes, it’s possible the hamburger’s origins stretch back to the Mongol hordes who made their way into Russia with their trail-ready raw meat. It’s possible that, centuries later, German sailors returned home from Russian ports craving the chopped meat patties they ate abroad and their wives insisted on cooking it.

But whatever the evolution actually entailed, by the latter half of the 19th century, chopped meat patties were known in the U.S. as “Hamburg steaks,” which devolved over generations of hurried, American speech to “hamburger.”

Edge explores regional recipes as well as historical alterations, such as the Depression-era innovation of adding bread crumbs to the ground beef to “stretch it out.”

It’s not the provenance, but rather the simple persistence of the hamburger during the century of American ascendancy that so closely ties to a national identity. It’s a proletarian food item that changed along with American industry. Henry Ford’s assembly line revolutionized the manufacturing process, and Ray A. Kroc of McDonald’s applied it to the meat patty. The hamburger is inextricable from industrialization now — a readymade, generic food item available instantly with no fuss. The flipside of this association is that the hamburger is also a symbol of the corporate homogenization of culture across the world, as well as a symbol of excess and gluttony. Of course, it’s also an emblem of “traditional” masculinity, as well as childhood innocence and anti-intellectualism. That’s pretty versatile for a slab of ground meat on a bun.

Anyway, whether you’re curious about how the burger was born, what the burger means, how to make the meatiest burger or how to make a meatless burger, Queens Library has you covered. Come in, check out a book and learn a little more about one of America’s iconic foods.

Queens Library at Woodside invited toddlers and their caregivers to celebrate Submarine Day, observed on April 11--the day the United States bought the U.S.S. Holland. We used pieces of an old puzzle and drew our own submarines. Then we added magnets to the backs of our puzzle pieces to make puzzle magnets.

April showers bring May flowers! In the spirit of encouraging more rain so that more flowers can bloom, children at Queens Library at Sunnyside were invited to make rain sticks. The supplies needed for the project? Simple! An upcycled tissue paper roll, a cloth to cover it, and beans to fill inside so children will be able to mimic the sound of rain when they shake their sticks. Materials for the Arts generously donated the beans and fabric we used for this project.

As a part of the Earth Week Film Festival at Queens Library, Queens Library at Astoria invited patrons to come and view the 2008 Sundance Film Festival award-winning documentary "Fuel," directed by Josh Tickell. "Fuel" is a film about the America’s addiction to oil and calls for society to start relying on more sustainable, environmentally-friendly forms of energy.

When I was an undergrad English major I took a course in American Literature after World War II. On the first day of class, the professor said, “This is a rare chance to read several of the same books as a group and then discuss them.”

I realize now how right she was. Reading is such a solitary act that people usually don’t get to talk about it. That’s what makes Queens Library’s book clubs so great — they’re a special way to share, learn, and expand one’s understanding of the chosen books. We’re good at running them, too.

In 2004 I started my Queens Library career at Richmond Hill. The Friends group there had an active book club. The manager at the time asked me if I could host them and I got excited about it. Since then, I have learned a few things about running and participating in book clubs:

1.) The first rule of Book Club is, ALWAYS READ THE BOOK. One month, we chose The Master Butchers Singing Club by Louise Erdrich, and I had read that a few years prior, and enjoyed it. So I thought since I already read it, I didn’t have to read it again. I was lost as participants brought up details of the characters or particular scenes.

2.) It can be tough to schedule, but try to time your reading so you finish a day or two before the meeting. If you can’t contribute to the whole discussion, the other participants will know quickly.

3.) I always think carefully about what books to pick: People don’t always want to take on novels that are the size of phone books. In 2007 I got a promotion to Assistant Manager at Hillcrest Community Library, and I decided to do a Classics book club in the evenings. One month early on, I chose Of Human Bondage. For about four days prior to the meeting, I stayed up until 3 a.m. each night and was able to finish it. But no one showed up to the book club meeting!

4.) You never know what great things other participants will share with you. I remember mentioning The Heart is a Lonely Hunter at one of the Hillcrest meetings, and someone recalled how she talked to Carson McCullers several times on the phone near the time of the author’s death.

5.) It takes different approaches to engage different book clubs. My strategy is first to see if anyone had strong opinions about the book. Then I see where the conversation goes. Anywhere between 5 minutes and 20 minutes we refer to discussion topics I’ve printed off the internet. My club at Seaside voted on what to read. I’d look up about twenty titles, and we simply picked three or four for a season.

6.) When people get really involved in book clubs, not even a natural disaster can stop them. I transferred to the Peninsula Library in April 2012 and started a “classics” book club there, drawing between five and 12 people regularly. Then Superstorm Sandy hit and destroyed our library. For months, the only library service was in the book bus parked out front. But three book club members came to me and insisted we keep going. In February, after a temporary trailer was set up, we started again, and we’re being ambitious. For April we scheduled The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn at the same meeting. In summer perhaps we’ll do Shakespeare. At the March meeting a participant came from Manhattan because she relocated there.

I feel fortunate that I’ve been able to do book clubs as part of my work. It’s a great way for our customers to take reading to the next level and discuss concepts beneath the surface, and it’s a way for me to better get to know the people who use my library regularly. I’m hoping to take part in book clubs at work for the rest of my career.

Check out our website for a Queens Library book club near you!

Picture books are just for children, right? Not always so.

Lane Smith’s picture book, It’s a Book has the look and feel of a book for the very young, with its thin, flat shape, its brief text, and abundance of charming, colorful illustrations. And it is typical child fare in that it is an animal tale with its three characters: a mouse, a jackass, and a monkey. The animals interact with lively questions from the digital and web savvy donkey about the monkey’s book, including “Can it text? Blog? Scroll? Wi-fi? Tweet?” and the monkey’s mostly patient refrain-type answer, “No, it’s a book.”

But it is also a book for adults for the following reasons. First, it deals with the hot topic, “Are books dying or dead?”—a current underlying anxiety for avid readers of the traditional, print book that is addressed with humor, as a battle between the old and the new, with a surprising conclusion. Second, a possible pile-up of literary references and allusions has greater appeal for adults. Robert Louis Stevenson’s adventure classic enjoyed by children, Treasure Island (1883) is of course the unstated title of the book the monkey is reading in the story. But there may also be allusions to The Life of Pi (2001) author Yann Martel’s latest literary reference laden book entitled Beatrice and Virgil (2010), which concerns a monkey and donkey; and so also allusion to Dante’s Divine Comedy (1307-); and so on. Finally, the last line in It’s a Book includes a double-entendre meant for adult ears. It, as well as the entire book, begs discussion and examination, a good thing for adults and children when it comes to the illustrated and written word.

Tags

Vicki Myron is the genius behind several books — with options for kids and adults — that happily star both a cat and a library, much to the delight of that wonderful segment of the population, that group of people who prize books and animals, probably more than nearly everything else!

First there’s Dewey: The Small-Town Library Cat Who Touched the World, by Vicki Myron, with Brett Witter, which as the title suggests is the biography of a cat. And what could be better? We are introduced to Dewey as a kitten in the first chapter. It is a bitter-cold January morning in Spencer, Iowa, in 1988 when an abandoned, nearly frozen baby feline is found in an open metal library book drop-box by library director Vicki Myron. The kitty is adopted by the library, named Dewey Readmore Books, and in the following 26 short chapters we read stories of survival and life lived with grace.

Although Dewey is the hub around which the wheel of the story turns, the author paints picture spokes of the surrounding worlds which he affects: Ms. Myron’s own life — which is not without hardship; the town of Spencer, its community and library; the Iowa heartland; America; Japan; and other communities small and large.

For those who enjoy Dewey, there is a sequel, called Dewey’s Nine Lives: The Legacy of the Small Town Library Cat who Inspired Millions. And also two new books for children: Dewey, the Library Cat: A True Story and Dewey’s Christmas at the Library. Copies of all of these Dewey books are available at Queens Library.

Sam Weller, an associate professor at Columbia, was Ray Bradbury's chosen biographer. He is also the author of Listen to the Echoes: The Ray Bradbury Interviews and Shadow Show: All New Stories in Celebration of Ray Bradbury.

Saturday, April 27 @ 12 p.m., ONLINE: Sam Weller will take your questions about the author, Fahrenheit 451 and more on our website. Post a comment on this blog post any time before Saturday and during 12 to 1 p.m. on Saturday and you'll get a reply from Weller himself. You can join us for a discussion on Facebook as well.

Saturday, April 27 @ 2 p.m., Queens Library at Flushing: Learn about Bradbury’s contributions to popular culture and how he wrote Fahrenheit 451. Copies of Weller’s books will be available for purchase and signing. Enter a raffle to win a copy of Fahrenheit 451 and an audio guide to the book. You must be present to win.